Principles of Newtonian mechanics

Fondamental : First law of motion : principle of inertia

« An object remains at rest or in a uniform rectilinear motion, unless a force is acted on it and forces it to change direction ».

This principle is only viable in inertial frames of reference.

Another version exists :

There exist a set of frames of reference, qualified as inertial (or Galilean), in which an isolated object is either at rest or in a uniform rectilinear motion.

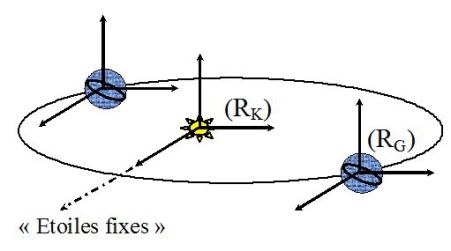

Fondamental : Inertial frames commonly used

An inertial frame is one in which the principle of inertia holds true.

The Kepler frame : the frame in which the origin is the center of the sun, and the three axes are oriented towards « fixed » stars.

The geocentric frame : its origin is the center of the earth, its axes are parallels to the ones in the Kepler frame.

The terrestrial frame (the frame of the laboratory) : the one commonly used.

All inertial frames of reference are translating uniformly one in relation to the other.

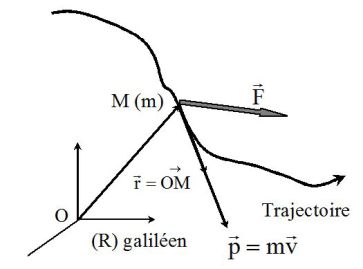

Fondamental : Second law of motion

It is used to calculate changes of momentum\( \vec p\) that are caused by resulting forces \(\vec F\) on a punctual objet (of constant mass \(m\)).

In an inertial frame, the second law is :

\(\frac {d\vec p}{dt}=\frac {d(m\vec v)}{dt}=\vec F\)

In an inertial frame, we consider \(n\) material points Mi of mass \(m_i\).

The motion of the center of mass of a system of material points is the same as a point which has the total mass of the system, to which is applied the sum of external forces applied on the system (according to the third law, the sum of the internal forces is equal to zero) :

\({m_T}\frac{{d{{\vec v}_G}}}{{dt}} = {\vec F_{ext}}\)

Where \(m_T\) is the total mass of the system.

The center of mass G of \(n\) material points Mi of mass \(m_i\) is the barycenter of the points divided by the mass of each point :

\(\sum\limits_i {{m_i}\overrightarrow {G{M_i}} } = \vec 0\)

If O is the origin of the frame, then :

\(\overrightarrow {OG} = \frac{{\sum\limits_i {{m_i}\overrightarrow {O{M_i}} } }}{{\sum\limits_i {{m_i}} }} = \frac{{\sum\limits_i {{m_i}} \overrightarrow {O{M_i}} }}{{{m_T}}}\)

Fondamental : Third law

If a body \(A\) exerts a force \(F_{A/B}\) on a body \(B\), then this body \( B\) exerts on \(A\) an opposite force :

\(F_{B/A}=-F_{A/B}\)

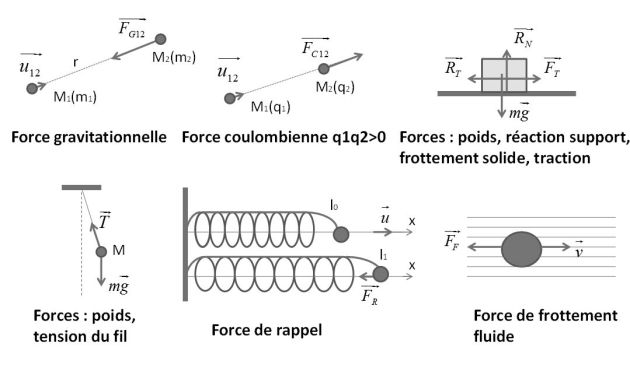

Exemple : Examples :

Fondamental : Torque and angular momentum :

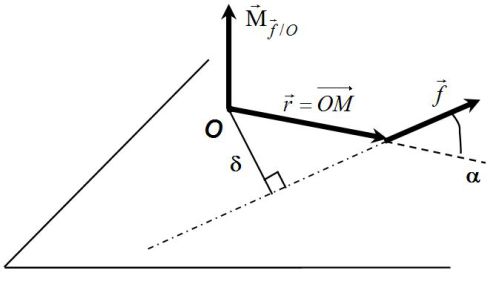

Let O be a fixed point in an inertial frame of reference.

A material point M as a velocity \(\vec v\) in this frame.

A force \(\vec f\) is exerted on it.

Let :

\(\vec L_O=\vec {OM}\wedge m\vec v\)

Be the angular momentum of M with respect to O.

It follows that :

\(\frac {d\vec L_O}{dt}=\vec {OM}\wedge \vec f=\vec M_{\vec f/O}\)

Where \(\vec M_{\vec f/O}\) is the torque of \(\vec f\) with respect to O.

Interpretation :

The norm of the torque of \( \vec f\) with respect to O is : (see figure)

\(\left| {{{\vec {\rm M}}_{\vec f/O}}} \right| = rf\sin \alpha = r\delta\)

\(\delta\) is the « moment arm » of \(\vec f\).

The moment arm (lever arm) of a force is the perpendicular distance from the line of action of the force and point O.

In other words, moment arm determines the quality of the torque.

Fondamental : Kinetic Energy and Work-Energy theorem

The second law of motion is applied to a point in an inertial frame of reference (R) :

\(\vec f = m\frac{{d\vec v}}{{dt}}\)

We dot-product by the velocity vector :

\(\vec f.\vec v = m\left( {\frac{{d\vec v}}{{dt}}} \right).\vec v\)

We have :

\(m\left( {\frac{{d\vec v}}{{dt}}} \right).\vec v = m\frac{d}{{dt}}\left( {\frac{1}{2}{{\vec v}^2}} \right) = \frac{{d{E_c}}}{{dt}}\)

Then :

\(P=\vec f.\vec v = \frac{{d{E_c}}}{{dt}}\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;or\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\vec f.\vec v\;dt =\delta W=d{E_c}\)

Two ways to write it :

The variation of kinetic energy of a material point is equal to the sum of the work of the forces that are applied to it. (Work energy theorem)

The power of the forces is equal to the rate of change of kinetic energy.

Fondamental : Mechanical energy and integrals of motion

Force | integrals of motion |

Tension d'un ressort | \(\frac{1}{2}m{v^2} + \frac{1}{2}k{x^2} = {E_{m0}}\) |

Champ de pesanteur | \(\frac{1}{2}m{v^2} \pm mgz = {E_{m0}}\) |

Champ gravitationnel (newtonien) | \(\frac{1}{2}m{v^2} - G\frac{{mM}}{r} = {E_{m0}}\) |

Champ électrostatique (coulombien) | \(\frac{1}{2}m{v^2} + \frac{1}{{4\pi {\varepsilon _0}}}\frac{{qQ}}{r} = {E_{m0}}\) |

Exemple : escape velocity (gravitational force)

What is the minimum initial velocity \(v_0\) required to make a material point on the surface of the Earth escape Earth's gravitational pull ?

The material point has to reach infinity (where potential energy is zero) with no velocity (to have the smallest \(v_0\)). Then :

\({E_{m0}} = {E_c} + {E_P} = \frac{1}{2}mv_0^2 - G\frac{{m{M_T}}}{{{R_T}}} = 0\)

So :

\({v_0} = \sqrt {\frac{{2G{M_T}}}{{{R_T}}}}\)

With :

\({g_0} = \frac{{G{M_T}}}{{R_T^2}} = 9,8\;m.{s^{ - 2}}\;\)

It follows :

\({v_0} = \sqrt {2{R_T}{g_0}} = 11,2\;km.{s^{ - 1}}\;\;\;\;\;\;\;({R_T} = 6\;370\;km)\)